Data Companies Are Watching Me

00. Introduction

I live in the northern part of San Antonio, Texas. This is a new development, since I moved houses last year. I enjoy visiting museums, eating at my favorite restaurants, spending time with family in the area, and more. Working remotely, I often have to travel for work to the Duo headquarters in Ann Arbor, Michigan, or the Cisco offices in California.

But if you’re a location data broker, you already know all that.

Every day, code embedded in mobile applications silently collects the location of hundreds of millions of unsuspecting users just like me. This data is purchased by location data brokers who use it to offer marketing analytics, provide targeted advertisements, or simply resell access to the data to other companies. The individuals installing the apps are usually only opting into location collection under the assumption that it’s required for the app to function (for example, for a weather app to give a local forecast).

We often talk about this data through the lens of bulk collection, but it’s important to remember that behind each dot on a map is a person going about their day. To get an idea of just how invasive and personal this data can be, I requested my own data from 14 companies that specialize in collecting and selling location data.

In this post, I’ll show how I requested my data from these location data brokers, detail what information I received, and talk through why the existing rights and processes just aren’t working for the average person.

01. Requesting My Data

Companies operating in different parts of the world are required to comply with privacy regulations. Some of these regulations, such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), allow residents of California to make requests to opt-out of the sale of their personal data, as well as request to see what personal data the company has collected about them. However, many companies will honor CCPA requests whether or not the individual is actually a California resident.

I submitted CCPA data access requests to 14 companies (you can find the full timeline below). I made sure to include with each request that I am a resident of Texas, not California, with the hope that companies dedicated to transparency would be willing to fulfill the request. Each company had a specific way to submit the request. Some were via emails, some had a dedicated web form, and others required me to download a mobile application to submit the request.

I wasn’t optimistic. Since I work in the security industry, I'm cautious about which apps I install on my phone, so I assumed it’d be unlikely any company had data about me.

Out of these 14 requests:

- 5 said they could not verify me according to CCPA requirements (see “The Anonymity Loophole” below)

- 3 said they had no data about my mobile device

- 3 declined to fulfill requests from non-California residents

- 2 still haven’t responded after nearly two months

- 2 companies, Unacast and Quadrant, automatically subscribed the email address I used to submit the data access request to their marketing emails.

- 1 sent me my data.

Reveal Mobile was the only company to provide my data to me on my initial request. To their credit, they promptly and kindly provided my data to me even though I’m outside of California, which is a practice I’d encourage other companies to follow.

While I discuss the data I got back from Reveal Mobile here, each of these companies collect location data from millions of people every day. Most of these companies claim to operate with transparency, yet Reveal Mobile was one of the only ones (besides those that claim they didn’t have data on my device) that promptly provided my data to me based on my initial request.

That being said, let’s dive into the data.

02. What I Got Back

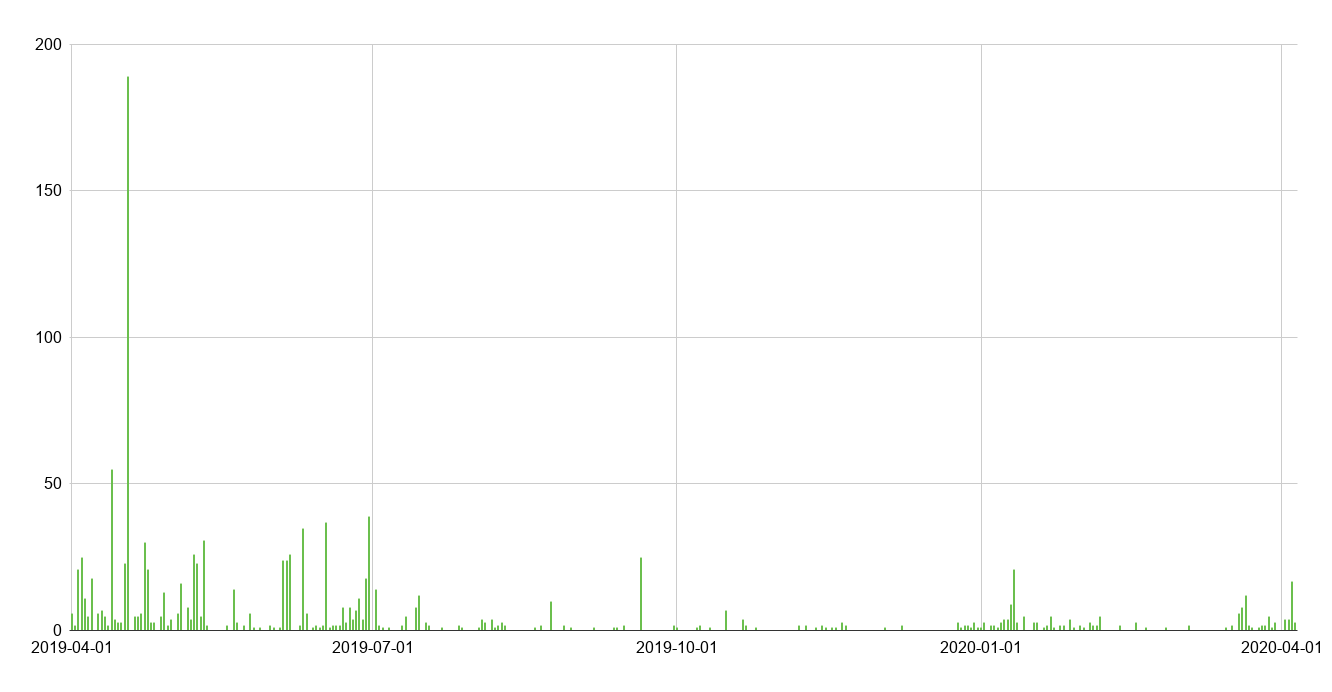

The data included over 1200 records from April 2019 to April 2020. Many days just had a few records, while others would have upwards of 50, with one day having a peak of 189 records. Each of these records is generated when a mobile application on my phone sends my current location either directly to Reveal Mobile or to a service provider which then forwards the data upstream.

In terms of volume, this appears to be normal. According to location data company Quadrant’s Data Quality Dashboard, 72% of devices report less than 50 events per day:

Source: Quadrant March 2020 Dashboard Report

Each record in the dataset had the following information:

- Event Time

- Mobile Ad ID

- Operating System (e.g. "ios")

- IP Address

- Horizontal Accuracy

- Latitude

- Longitude

To visualize the data, I used kepler.gl. Here’s a timelapse showing my activity in San Antonio over the past year according to the data. Note that I’ve chosen to bin each hexagon to a 1km radius to roughly anonymize my location, even though the data itself has my exact location:

In this visualization, it’s clear when I moved to a house further north last summer. The data watches as I travel around my community, and you see a sudden freeze in my location around late January as I opt to shelter in place due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

And it’s not just San Antonio. The data also watched me as I traveled for work to Duo’s headquarters in Michigan and to Cisco’s headquarters in San Jose. It shows when I took family vacations to San Diego and the Gulf coast.

It’s not immediately clear which mobile application is collecting and sending my data. For an experiment, I proxied traffic from my mobile device for a week to try and determine which applications were collecting my location data. While I did see my location data being sent out to various advertising companies and service providers for the apps themselves, I didn’t see any results that conclusively tied back to Reveal Mobile.

And this isn’t surprising. Like many location data providers, Reveal Mobile’s privacy policy suggests it collects data directly from its SDK as well from “server-to-server feeds,” making it difficult to know how my data was collected and how widely it was shared.

While Reveal Mobile’s privacy policy may allow for this kind of data sharing, I didn’t individually intend for my location information to be collected and sold when installing a mobile application. And even more, it’s frustrating not fully knowing what data has been collected or shared and by whom.

03. What Made This Difficult

As I set out to answer the question “what data do companies have on me?”, I came to realize that there are multiple problems with the current state of the industry which make it incredibly difficult for the average individual to control their data.

Privacy Regulations Aren't Widespread

While there has been increased focus and discussion regarding privacy laws around the world, there are two well-known laws that allow certain people to better understand and control how their data is being used. These are the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which applies to companies that operate in the EU and/or process personal data collected from people in the EU, and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which applies to companies that process personal data of California residents.

This brings up the first major problem with the state of our privacy regulations - that they don’t apply to everyone in a uniform manner. Texas does not currently have consumer privacy legislation similar to the CCPA. As a result, I didn’t have any meaningful other options than making these requests under the CCPA and hoping that companies would be willing to fulfill them out of a sense of transparency beyond what the law requires.

No Consistent Control Over Data

So let’s say that I’m a resident of an area that has strong privacy regulations (after all, one can dream, right?). The next issue is that every company has its own way to request data, or to opt -out from the sale of data. During my research, I came across forms submitted via the company’s website, emails to particular addresses, or even forcing people to install a mobile app the company created solely for the purposes of managing opt-out requests.

Individuals can opt-out of certain forms of data collection by opting out of targeted advertising. This essentially zeroes out the device’s Mobile Advertising ID (“MAID”), or sets a flag telling applications not to use it. However, that doesn’t help the owner understand what data has been collected about their device so far, or prevent the collection or sale of that data.

No Way to Natively Find Your Mobile Ad ID

Let’s assume that I’m a resident of an area that has strong privacy regulations, and I’ve found the form I need to submit to make that request. Since location data is tied to a MAID, companies will request your MAID in the data access request form. The problem is that getting the ID for a device isn’t straightforward on some platforms.

Android users can generally find their MAID in their device settings under Settings > Google > Ads. However, there is no native way for iOS users to view their advertiser ID (called an “IDFA”). You can reset the IDFA, but you can’t view the current one for your device. Instead, device owners are required to install a third-party application in order to view their IDFA, exposing users to the risks associated with installing third-party applications.

The Anonymity Loophole

But let’s say that I’ve managed to find my MAID and submitted a data access request to a company. There’s still no guarantee that it will be fulfilled.

The most common reason companies didn’t fulfill my data access requests was that they claimed they weren’t able to verify my identity according to the requirements outlined in the CCPA. They may say this is due to the fact that they only store the Mobile Advertiser ID, and not any “personally identifiable information.”

While I can appreciate the goal of preventing fraudsters from accessing my data, this can be used as a loophole. The data itself is personal to the extent that it can accurately track my location at points throughout the day, roughly pinpointing where I live and work. So it’s frustrating to be told that my identity cannot be verified, and as a result I cannot determine what precise data a company is collecting about me. At this point, the company effectively has all of the information it needs to know that there is a unique user out there, it’s just not putting that together by itself in order to identify me by name or making the association to provide my data to me.

For companies that do offer a way for requesters to verify their identity, the verification method can differ significantly. Some companies only require a checkbox to assert that the person making the request is the owner of the device. Others may require a screenshot of the device’s MAID, or require the user to install their app so they can inspect the MAID themselves. There were also some which asked for three unique recent addresses to help verify that the locations match up with their records, which proved to be difficult during stay-at-home orders.

04. Wrapping Up

Even as a security professional who is careful about which apps I install on my phone, I’m not immune to having my location data collected and sold. And the data shown above is from one company covering a single device. The reality is that dozens of companies are monitoring the location of hundreds of millions of unsuspecting people every single day.

The lack of widespread privacy regulations, combined with technical limitations and lack of consistency and transparency by the companies involved, creates conditions where the average person doesn’t stand a fighting chance to know how their data is being collected and used.

One way to address this problem is to shine a light on it. To that end, I’ve included a table below that summarizes the access requests I submitted, giving links on where you can go to submit your own. As for me, I’m going to go back to living my life, ordering from my favorite restaurants, and visiting with family.

You know where to find me.

05. Request Timeline

| **Company** | **Date Submitted** | **Date Responded** | **Request Method** | **Result** | |---|---|---|---|---| | Cuebiq | 04-27-2020 | 05-05-2020 | Mobile App | No data\* | | Dstillery | 04-17-2020 | | Website | No response | | Factual | 04-15-2020 | 04-21-2020 | Website | Couldn't verify identity | | Fysical | 04-19-2020 | 04-20-2020 | Email | Not a CA resident | | Gravy Analytics | 04-19-2020 | 04-29-2020 | Website | Couldn't verify identity | | Locomizer | 04-22-2020 | | Email | No response | | Quadrant | 04-22-2020 | 05-07-2020 | Website | No data | | Reveal Mobile | 04-07-2020 | 04-15-2020 | Website | Received data | | Tamoco | 04-22-2020 | 05-05-2020 | Email | No data | | Tutela | 04-19-2020 | 04-20-2020 | Email | Couldn't verify identity | | Ubimo | 04-19-2020 | 05-12-2020 | Email | Not a CA resident | | Unacast | 04-17-2020 | 07-08-2020 | Website | Couldn't verify identity | | Venntel | 04-22-2020 | 04-24-2020 | Website | Couldn't verify identity \*\* | | XMode | 05-20-2020 | 06-01-2020 | Email | Not a CA resident

* Shortly before submitting my request to Cuebiq, I had reset my Mobile Ad ID for other parts of this research. This is why it’s expected that they did not have any data for the new ID.

** Venntel (and Gravy Analytics) both ask for three unique recently visited addresses to help verify the requestor’s identity. Neither were able to identify me based on the addresses provided. After following-up with Venntel to provide even more addresses, they were able to match two of them, which allowed them to share the types of data they collected on my device, just not the data itself.